Argentina

Argentina defaulted on $100bn of debt in 2001-02, at the time the largest sovereign default in history.

FT, July 31, 2014, 12:28 am

"All of our economy ministers have gone to Harvard -- to learn what? To rob the country?" said one frustrated woman, voicing widespread anger at a political class seen as corrupt and inept.(FT)

With Argentina devaluing its peso over the weekend,

the conventional economic wisdom finally got its way.

Wall Street Journal, editorial, 2002-01-08

Since 1991, the peso has been fixed to the dollar

at a one-to-one rate under a currency board system.

1 Peso = 1

Dollar

Members of the opposition fantasise about President Mauricio Macri fleeing the presidential palace in a helicopter

— just as the president did last time an IMF programme failed in Argentina before its 2001 crisis.

FT 31 August 2018

Argentina continues to suffer from deepening market panic.

FT 30 August 2018

Interest rates at world highs. The largest International Monetary Fund programme in history. A pro-business government, with a technocratic cabinet that world leaders are keen to support.

And yet Argentina continues to suffer from deepening market panic.

Argentina peso boosted as central bank auction deemed a success

The central bank agreed to pay 40 per cent interest rates on the notes

FT 15 May 2018

With the amount of securities at stake equal to almost half the value of Argentina’s $53bn foreign exchange reserves, the central bank agreed to pay 40 per cent interest rates on the notes to maintain investor interest.

“This could be a turning point,” says Marcos Wentzel, a partner at Puente, a local investment bank

What could possibly go wrong?

Bond investors do not care if Argentina is solvent in 100 years

When Argentina issued its so-called “century bond” in June last year, many held it up as the peak of bull market insanity.

After all, what sane individual lends money for 100 years to a serial-defaulter?

Robert Smith FT Alphaville 11 May 2018

After the Latin American country began discussions with the International Monerary Fund earlier this week, the schadenfreude in some quarters was palpable.

Argentina sold the debt at a steep discount, offering the notes to investors at 90 cents on the dollar.

Duration is not the same as maturity: no investor bought Argentina’s debt hoping their grandchildren would get the money back in 2117.

Instead, duration is the amount of time it takes to earn back the principal amount you originally invested.

Argentina’s coupon of more than 7 per cent meant its initial duration was just over 12 years.

Argentina’s plea for IMF help is a reminder of global fragility

If the country’s turmoil spreads, the safety nets will undergo a severe testing

Gillian Tett FT 10 May 2018

A year ago, Argentina was the darling of global investors. So much so that, when it issued a pioneering 100-year bond with a yield of just 7.9 per cent, investors gobbled it up,

ignoring the fact that the country has defaulted eight times in the past 200 years.

After all, as Jay Powell, the Fed chair, observed this week: “Some investors and institutions may not be well positioned for a rise in interest rates.”

The Economist explains

Why has Argentina called in the IMF?

The Economist 11 May 2018

Between April 23rd and May 4th the central bank hiked interest rates by 12.75 percentage points to 40% and sold $5bn of its currency reserves.

Argentina settles 15-year debt battle with $4.6bn deal

Telegraph 29 Febr 2016

The conflict dates back to 2001 when Argentina defaulted on nearly $100bn in debt.

Nearly all the country's creditors eventually accepted to write off 70pc of their bonds in a restructuring that was meant to allow the country to get back on its feet.

But 7pc of the creditors refused. Elliott, a New York hedge fund which bought up debt after the default, sued together with Aurelius for full payment on the face value of the bonds.

Argentine Bonds Decline as Default Triggers $1 Billion of Swaps

Bloomberg Aug 2, 2014

What Happens Now That Argentina Is in 'Selective Default'

It’s up to the International Swaps & Derivatives Association to determine whether a default has occurred.

If it does, holders of the credit default swaps are entitled to a big payment.

Business Week, July 30, 2014

Argentina defaults after last-minute talks fail

Argentina defaulted on $100bn of debt in 2001-02, at the time the largest sovereign default in history.

FT, July 31, 2014, 12:28 am

Q&A: Argentina on the brink of default

FT July 30, 2014 4:09 pm

The holdout creditors refused debt restructurings after Argentina’s 2001 default, instead suing Argentina for full payment.

Although Judge Griesa ruled in their favour in November 2012, Argentina has persistently refused to pay up,

most recently on the grounds that payment would violate the so-called RUFO (Rights Upon Future Offers) clause in the restructured debt.

Argentina fem dagar från statsbankrutt

Före den 30 juli måste Argentina nå en uppgörelse med tvistande hedgefonder.

Men om landet betalar befarar Argentinas regering att andra obligationsinnehavare ska begära samma behandling

SvD Näringsliv 25 juli 2014

BBC Why the bond markets fear Argentina's debt crisis

Investors are intently watching two separate stories in the bond market Monday that could have rippling effects,

challenging the traditional notions of how bonds are paid.

Argentina is expected to enter technical default for the second time in less than 15 years

as the pariah of the debt markets negotiates with creditors in the wake of a Supreme Court ruling

mandating payouts to a group of hedge funds.

MarketWatch June 30 2014

The South American nation’s negotiations are already rewriting the rules of sovereign debt restructuring.

Argentina’s Sovereign Bondage

Anne Krueger, Project Syndicate 9 July 2014

Things sometimes go wrong. Sometimes this is due to bad luck and sometimes to irresponsibility.

But society needs a way to allow people to start over again. This is why we have bankruptcy.

Martin Wolf, 24 June 2014

Usually, it is countries with a history of fiscal irresponsibility that find themselves obliged to borrow in foreign currencies.

The eurozone has put its members in the same position: for each government, the euro is close to being a foreign currency.

When the costs of servicing such debts become too high, then restructuring – default – becomes necessary.

A better way must now be found.

Ett land som går med i EMU får lämna ifrån sig inte bara sin valutareserv utan även sin sedelpress.

Ett medlemsland i EMU blir som vilken låntagare som helst.

Som Göteborgs kommun,Fastighetsaktiebolaget Hufvudstaden, AB Näckebro, Gävleborgs landsting eller Åre Kommun.

Rolf Englund på Internet 1997-04-22

Om man har en sedelpress går man inte i konkurs.

Det var varit det till synes självklara budskapet på denna blog ett antal gånger, första gången i november 2011.

Why eurozone should monitor US Supreme Court decision on Argentina

Can bondholders demand full repayment of what they lent to a country even when others have settled for a haircut?

Linda Yueh, BBC Chief business correspondent, 13 January 2014

Kreditvärderingsinstitutet S&P har skrivit ned

Argentinas kreditvärdighet från CCC+ till CCC-

Det är den sämsta kreditvärderingen något land har just nu.

SvD Näringsliv 18 juni 2014

Resultatet kan bli att landet tvingas ställa in betalningarna på alla sina utlandslån.

På grund av sin dåliga kreditvärdighet var Argentina tvunget att utfärda obligationerna i New York,

under amerikansk lagstiftning. Domen innebär att Argentina inte kan betala nya obligationsägare om de inte samtidigt betalar vad de är skyldiga de som har de ursprungliga obligationerna. Dessutom ger den kreditorerna rätt att använda amerikanska domstolar för att hitta Argentinas tillgångar.

Enligt domstolen måste Argentina betala 1,3 miljarder dollar.

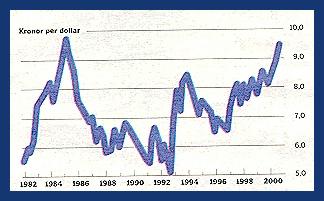

Jfr Carl Bildts försök med fast växelkurs vid samma tid

President Cristina Fernández of Argentina has raised the prospect of a sovereign default,

saying that her government could not succumb to the “extortion” of a US Supreme Court decision

that orders it to repay $1.5bn to “holdout” investors before servicing its restructured debt.

Financial Times, 17 June 2014

US Supreme Court on Monday said Buenos Aires had to pay $907m to the investors who had not joined restructuring programmes or lose the ability to use the US financial system to pay an equal amount due by June 30 to holders of other Argentine bonds.

Under perioden 2003-2007 var hon även Argentinas första dam då hennes man var president.,, Wikipedia

Argentina has reached an agreement with the Paris Club group of international creditor governments

to repay its overdue debts over a five-year period. The deal covers Argentine arrears of some $9.7bn.

During the last weeks of 2001 the Argentine government defaulted on public debt totalling $132bn.

BBC 29 May 2014

In search of a better bailout

Proposals to overhaul sovereign debt restructuring are raising fears of unintended consequences

“When Armageddon hits you’re always less prepared than you think.”

FT 26 January 2014

For two years Petros Christodoulou had one of the world’s toughest jobs. As head of Greece’s debt office

Mr Christodoulou, who had spent years as a trader at JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs, held his nerve but the pressure was too much for some of his staff, who quit.

Once the restructuring was complete, he too left Greece’s debt management office.

“It was a tremendously strenuous situation,” he admits.

“When Armageddon hits you’re always less prepared than you think.”

Argentina is an economic basket case. It is that simple. The country never seems to be able to emerge from its problems.

The key reason is that the country is extremely weak constitutionally and institutionally and as a result

the country has some of the worst policy makers in Latin America (if not in the world).

The Market Monetarist 4 January 2014

Nice chart

I stole the graph from Wikipieda, but you can find a similar graph in any intermediate microeconomic textbook. I suggest that Augusto Costa and his boss president Cristina Kirchner try to get hold of such textbook very soon so this foolishness can come to an end once and for all!

Argentina has been told again it must pay back more than $1.3bn to a group of investors - 11 years after its record debt default.

A New York appeals court unanimously rejected every Argentine argument against the payout.

BBC, August 25, 2013

The decision is the latest twist in the long-running legal saga.

Argentina refuses to pay anything to investors who declined to participate in a previous debt reduction deal involving most of the nation's lenders.

Argentina will have to pay $1.3bn to hedge funds that refused to restructure their debts after the country’s 2001 default

The ruling raises the possibility that Argentina will default once more,

and if upheld represents a major chink in the armour of sovereign immunity against creditors that has largely reigned in international law for almost a century.

Financial Times, November 22, 2012

Peter Wolodarski, PJ Anders Linder och Grekland

Rolf Englund 20 maj 2012

Precis som i Grekland framkallade krisen i Argentina ekonomiska, politiska och sociala omvälvningar.

IMF krävde i likhet med dagens EU/IMF att Argentina skar ned ordentligt i sina utgifter för att få nya lån.

I efterhand har valutafonden medgett att man skrev ut en felaktig kur för Argentina.

År 2004 konstaterade IMF att man borde ha ändrat strategi när det stod klart att nya åtstramningar inte gick att genomföra.

Peter Wolodarski, Signerat DN 20 maj 2012

Den ordinerade krismedicinen, i praktiken ekonomisk svält, fungerar lika illa i Grekland som i Argentina 2001.

Som den irländske ekonomen Kevin O’Rourke frågade retoriskt häromdagen:

Varför ska man fortsätta på en kurs som ändå leder mot ett haveri?

Sannolikheten är hög att Grekland, precis som Argentina, till slut ”löser sina problem” genom att ställa in betalningarna, och kanske även lämnar euroområdet.

Berlin måste också överge sin egen dogm om att eurokrisen kommer att lösas genom att Sydeuropa svälter sig till återhämtning.

Inget talar för att besparingarna får fart på tillväxten inom överskådlig tid eller att väljarna accepterar utvecklingen.

Återstår för omvärlden att fortsätta skriva av skulder, samtidigt som ECB tillåter högre inflation och ser till att det europeiska banksystemet fortsätter att fungera.

Det ligger det i Tysklands absoluta egenintresse att förhindra en större kollaps för valutaunionen.

Om Grekland faller – vilket verkar troligt – kan mycket väl Spanien, Portugal, Italien och Irland stå på tur.

I förlängningen hotas hela EU-samarbetet

Top of page - News - Start page

For a vision of how the Greek debt meltdown is going to end,

look no further than the International Monetary Fund's post mortem into a similar crisis that came to a head almost exactly a decade ago

- Lessons From The Crisis In Argentina. Originally published in October 2003, this policy review document was

signed off by a then relatively unknown IMF official called Tim Geithner, now the US Treasury Secretary no less.

Jeremy Warner, Daily Telegraph, 4 July 2011

The parallels with Argentina are so strikingly exact as to bear repeating at length.

Substitute the word Greece for Argentina in the IMF's analysis, and euro for currency board,

and you'd have a near perfect account of the present crisis, all written nearly eight years ago.

Here's what happened in Argentina.

Lessons from the Crisis in Argentina

Prepared by the Policy Development and Review Department

Approved by Timothy Geithner, October 8, 2003

While there are many similarities between the Greek and the Argentine experiences, as a member of the Eurozone,

Greece cannot inflate (and reduce its real debt burden) and it cannot devalue its currency. This is a severe constraint.

Peter Kretzmer and Mickey Levy, Vox 16 May 2012, tip Mattias Lundbäck

Argentina’s deepening recession, run on banks and associated social unrest in 2000-1 stemming from its own policy mistakes forced it to default and abandon its US dollar currency peg.

The Argentine peso depreciated dramatically. Inflation soared temporarily, battering standards of living. But the default and currency depreciation set the stage for a turnaround which, aided by a fortuitous bounce in commodity prices, spurred a strong export and investment-led economic rebound.

Can Greece learn the economic lessons Argentina missed?

By Robert Plummer Business reporter, BBC News 28 June 2011

Default, Devaluation, Or What?

it looks quite possible that Greece will spiral into domestic as well as debt crisis, and be forced to take emergency measures.

And that makes me think of Argentina in 2001

Paul Krugman May 4, 2010

What about an outright default? How bad could it be?

Well, it would be big. Bigger than Russia's 1998 default and Argentina's 2001 default put together, in fact.

Robert Plummer, BBC 28/4

Latvia - IMF experts were overruled by Brussels

Contrary to revisionist talk, Argentina was not a basket case.

Its imbalances were no worse than those of the Baltics, Balkans, Spain, or Greece, and arguably better.

The denouement sequence is worth rehearsing since it offers a crude guide for those with euro pegs in Eastern Europe,

and ultimately perhaps for Club Med inside EMU.

The explosive power of this broad group dwarfs Argentina.

Ambrose-Evans Pritchard, Daily Telegraph 14 Jun 2009

Latvia’s currency crisis is a rerun of Argentina’s

Devaluation seems unavoidable

Nouriel Roubini, Financial Times, June 10 2009

A market correction is coming, this time for real

Mr. Rhodes gained a reputation for international financial diplomacy in the 1980s for his leadership in helping manage the external-debt crisis that involved many developing nations and their creditors worldwide.

During that period and in the 1990s he headed the advisory committees of international banks that negotiated debt-restructuring agreements for Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay

William Rhodes, FT March 29 2007

The IMF ignored the problems created by Argentina's dollar peg and the resulting strong peso policy - which linked a sinking Argentine economy to a rising US economy and a rising dollar back in the late 90s.

Brad Setser blog 29/9 2005

The problem was not just that Argentina's monetary and fiscal policies were inconsistent with Argentina's exchange rate policies. That is an easy thing for the IMF to say - if you are willing to contract your economy enough with tight monetary and fiscal policies, and thus bring about enough deflation, a country can squeeze itself into any exchange rate.

The problem was that Argentina's exchange rate policies were inconsistent with growth in Argentina, since the needed adjustment could only come about through deflation. The IMF never said that.

Much of the recent strain associated with globalization can be linked to China's steadfast defense of its dollar peg, and its current policy of spending $300 billion, a bit over 15% of its GDP, to resist RMB appreciation. That has consequences.

Let us think the unthinkable:

Could the eurozone disintegrate?

The answer is yes.

If /Italy/ fails to rise to the challenge it confronts, a default or even a forced withdrawal

from the eurozone is perfectly conceivable.

Martin Wolf Financial Times 25/5 2005

The Bush administration could help here by telling the IMF to back off. Putting an end to the Clinton era of IMF bailouts

Wall Street Journal 21/6 2005

Argentina's collapse: A decline without parallel - The Economist

In the mid-1990s Argentina was lauded as an

economic miracle. Today, after three years of stagnation, it represents one of

the world's most intractable economic trouble spots.

Why?

BBC News Online maps the country's fall from grace.

Financial Times Special report: Argentina's economic crisis

Rolf Englund in Financial Times

(discusion) Argentina and Euroland

Date: Tue, 27 Mar 2001

Argentina gambled, and the gamble paid off. By bullying private creditors into accepting a pitiful settlement on its $100bn (£52bn) debt restructuring it has rewritten the rules of the game in emerging market finance.

It proved that debtor countries have a lot of power in their dealings with bondholders. This increases the risk involved in lending to emerging markets and should push up interest rates on emerging market debt.

Financial Times editorial 7/3 2005

The first priority is to deal with the 24 per cent of creditors who refused to sign up to the deal. Past successful restructurings achieved initial acceptance rates of about 95 per cent. The 24 per cent hold $20bn debt, $25bn with interest. Argentina has threatened to repudiate this. Such a ruinous strategy would invite decades of litigation. The fund /IMF/ would have to walk away. Better to reopen the offer for a limited period. Such an offer must be open to all creditors, not just the Italian retail investors whose plight evokes sympathy and demands an investigation into why they were sold high-risk Argentine debt in the first place.

The debt crisis that has taught lenders nothing

AND THE MONEY KEPT ROLLING IN (AND OUT, Wall Street, the IMF and the Bankrupting of Argentina

By Paul Blustein, PublicAffairs $27.50

Alan Beattie, FT February 16 2005

Blustein, a reporter on the Washington Post, has reprised the journalistic approach that made his first book, on the complex issue of the International Monetary Fund and the Asian crisis, unexpectedly readable. Through interviews with the leading figures in Argentina, on Wall Street and within the IMF, he reconstructs the riveting narrative of a nation that in 2001 committed the biggest sovereign debt default in history.

The IMF, wisely as it turned out, was initially suspicious of the dollar peg currency regime that Argentina adopted in 1991 and which proved the country's undoing. But the fund became impressed by the peg's early success...

Accordingly, it suppressed its misgivings about Argentina's inability to balance its budget and its consequent need to borrow dollars from the global capital markets at ever-higher rates to back the dollar peg. Far from imposing the "Washington Consensus" (the first component of which, let us recall, is fiscal discipline) on Argentina, the IMF was fatally complicit in its violation. As the crisis deepened in 2000 and 2001, the fund was so keen to avoid blame for pulling the plug that it continued to lend until all hope was extinguished.

The crisis was not primarily made in Washington. Blustein finds the real culprits in Buenos Aires and New York: the Argentines who peddled a falsely glowing vision of their country's economic renewal and the herd-like investors who believed the story or simply tracked the index of emerging debt.

One solution, which is targeted at private investors, is to swap existing bonds for new ones with the same face value, so a creditor who is owed $50,000 will get $50,000 - but not until 2038.

BBC 13/1 2005

Investors accepting this offer would have to endure 33 years of low interest rates starting at just 1.3%, gradually rising to 5.25%. The problem is that inflation would rapidly erode the cash pile, making it worth much less in real terms by the time it is due to be cashed in.

Top

Argentina's debt restructuring:

It is time for creditors to accept the current deal and move on...

Nouriel Roubini 12/1 2005

His site is at http://www.stern.nyu.edu/globalmacro/

Top

Argentina plans to repay all its $15bn debt with the International Monetary Fund,

the private creditors, who hold $81bn of defaulted bonds, are crying foul.

The score will be 20 per cent down for the IMF versus 75 per cent for the markets.

Adam Lerrick Financial Times 11/1 2005

The writer is director of the Gailliot Center at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, and chairman of the negotiation team of Abra, which represents European hold ers of $1.2bn of bonds in the Argentine restructuring

For the first time in the history of sovereign default, the implicit debt reduction that the official sector will absorb is far exceeded by the loss the private sector will be forced to swallow. If Argentina's restructuring, to be launched this week, goes according to plan, the score will be 20 per cent down for the IMF versus 75 per cent for the markets.

The IMF has always enjoyed a sacrosanct preferred-creditor status - to be paid first and in full before private investors get a penny. Payment is largely theoretical for, when problem loans become due, the IMF simply rolls over the financing without regard for risk or return. But, as creditors compete over a finite pot of money, the fund may be forced to accept write-downs. The IMF could find itself with a balance sheet as questionable as those of its developing-country borrowers and without the support of the rich nations that finance its high-profile rescues.

After years of over-spending by countries and over-lending by capital markets, the international financial system faces serious adjustment. There is now $1,600bn in emerging market sovereign debt with $400bn of government bonds in investor portfolios. Debt levels of 80 per cent to 100 per cent of gross domestic product, which were endorsed by the IMF as recently as 2001, are now deemed unsustainable; the current prescription is 20 to 40 per cent. Politicians now feel an obligation towards a new "preferred creditor" - a "social debt" to provide a better quality of life for a restive electorate.

The IMF prides itself on the fact that there has never been a default on its books. But as over-borrowed nations become unable or unwilling to honour their promises to pay, a series of contentious restructurings - of which Argentina is only the first -risks putting the IMF's senior status and its balance sheet in jeopardy.

Argentina has unveiled a new offer to the creditors it stopped paying almost three years ago.

Will this end the largest sovereign default in history?

The Economist 2/11 2994

The true extent of the haircut may not be clear until the new bonds first come on the market. But they are unlikely to be worth much more than 30% of the original value of the bonds they replace. By comparison, Ecuador offered creditors between 33% and 62% after its default in October 1999. Even Russia offered 35% after its 1998 default.

Argentina again

The latest IMF programme, which essentially rolls over loans from its outstanding exposure of nearly $15bn, is currently off track.

Financial Times editorial September 28 2004

Several structural issues remain unresolved, including reforming the banking system, finalising revenue-sharing agreements with the provinces and, most saliently, concluding negotiations with private investors who hold more than $100bn in defaulted sovereign debt. The Argentine economy's short-term recovery has given the authorities enough revenue to cope without rollover payments from the IMF for now. But if and when the tortuous debt negotiations are resolved and the programme resumes, the fund's problems will return.

In the absence of Argentine access to private capital markets or the willingness to run a bigger surplus before then, there is little that the IMF can do if Argentina threatens to default to it as well. The IMF's dominant shareholders have generally proved to have backbones as soft as marzipan when it comes to dealing with the Argentines.

The most important meeting between the Argentine government and

its private creditors over how to settle the world's biggest sovereign

debt-restructuring process.

More than two years have passed since the

country defaulted on almost $100bn of debt

Financial

Times 146/4 2004

More than two years have passed since the country defaulted on almost $100bn of debt, and the hundreds of thousands of European, Japanese and Argentine retail investors who bought the bonds have not seen a cent of their investments since.

"We want to start negotiating with the Argentines, to compare our [macroeconomic] assumptions with theirs and arrive at a mutually agreed settlement," Nicola Stock, co-chairman of GCAB, told the Financial Times this week.

Everything suggests he is likely to be disappointed. Since the beginning of March, when as part of the stand-by agreement Argentina promised it would "engage in constructive negotiations" with all representative groups, including the GCAB, the government has avoided the word "negotiation" altogether.

Instead, President Néstor Kirchner's administration has preferred more non-committal words such as "consultations", "talks" or "meetings". It has also said it will not discuss changing its initial offer to write off 75 per cent of the nominal value of the defaulted bonds - a proposal dismissed by investors.

The government pretends it will not

repay, while the IMF pretends it will not lend.

In the end, reality breaks

in: Argentina pays and the Fund lends it the money with which to do so.

Financial Times editorial 11/3 2004

If the Fund is to be the lender of last resort to countries in difficulty, it needs to be confident of being repaid. But, after the collapse of its pegged exchange-rate regime and default, Argentina fell into political and economic chaos. The IMF's hopes of repayment were deferred. In 2003, disbursements to Argentina covered 98 per cent of the repayments due. This year, again, disbursements from the Fund should cover the bulk of the repayments from Argentina.

The most controversial question outstanding has been Argentina's take-it-or-leave-it attitude to its creditors. "The authorities," noted Ms Krueger, "will work with the assistance of investment banks to establish a timetable and process that will ensure meaningful negotiations with all representative creditor groups." This appears to mark significant progress. If so, it also justifies the IMF's decision to make the disbursement of $3.1bn now due.

Who blinked?

Argentina has pulled

back from the brink of another default by paying back $3.1 billion it owed the

IMF.

All the same, there may be trouble ahead

Mar 10th 2004 From

The Economist Global Agenda

But Argentina gets something in return: later this month the IMF will recommend to its board that Argentina is paid the money back again, part of a $13.5 billion facility agreed last September. Relief all round.

Dissatisfaction with Argentina grew for other reasons. It attempted to deal only with bondholders prepared to sign a central register, and it refused formally to recognise the biggest creditor group, the Global Committee of Argentina Bondholders, who speak for owners of nearly half of the defaulted bonds. Now, as part of its deal with the IMF, Argentina says that it will recognise the committee, and that it will give formal powers to the banks it has appointed to deal with creditors. Mr Lavagna says that he will begin talks with creditors as soon as this month, and hopes to conclude negotiations by May or June.

Argentina on Tuesday agreed to make a

$3.1bn payment to the International Monetary Fund, narrowly avoiding what would

have been the biggest single default in the fund's history

Financial

Times 8/10 2004

Argentina is already in default with its private creditors after the country stopped servicing almost $100bn of debt in December 2001.

It is expected IMF management will recommend that the fund's board members formally approve Argentina's second review under the current standby programme. Formal approval, expected within about two weeks, would unlock funds about equivalent to yesterday's payment.

The agreement comes as the IMF searches for a new managing director after Horst Köhler, the fund's current head, resigned last week after he was proposed as Germany's next president. Jean-Claude Juncker, Luxembourg's prime minister, said on Tuesday he would back the nomination of Rodrigo Rato, Spain's economy minister, to spearhead global attempts to head off financial crises.

By late 2003, just three countries - Brazil, Turkey and

Argentina - accounted for 72 per cent of all IMF outstanding general

credit

Argentina has proved brilliant at exploiting its knowledge of the

IMF's vulnerability

Martin Wolf, Financial Times 10/3 2004

Total amounts outstanding to these countries are now 45.8bn Special Drawing Rights ($67.5bn), of which $28.1bn is to Brazil, $23.7bn to Turkey and $15.8bn to Argentina. The sums outstanding to these borrowers are 21 per cent of the IMF's total resources. Mr Köhler bet the ranch. In doing so, he also made big mistakes, notably in the loans made to Argentina in 2001. Above all, the Fund is underfunded for lending on this scale. As a result, it is at the mercy of its biggest borrowers. Argentina has proved brilliant at exploiting its knowledge of the IMF's vulnerability.

Finally and most important of all, the Fund needs to display convincing leadership on the issue that remains its reason for existence: global balance of payments adjustment. At present, that adjustment is working, or rather not working, in the most peculiar way: the world economy achieves a reasonable macroeconomic balance only by driving the US into ever-increasing current account deficit. This seems perverse in itself and is in all probability unsustainable as well.

Mr Köhler did his best as managing director. But everybody knew he was nobody's first choice. His successor needs the authority that can come only from a more open and transparent selection procedure. Unfortunately, that will not happen. The appointment seems unlikely to be quite as controversial as that of four years ago. But it will be the outcome of squalid horse-trading within the European Union, that self-proclaimed bastion of idealistic multilateralism. It should go without saying - but apparently does not - that this method of selecting the IMF's head is grotesque for an institution whose board prates about improved governance everywhere else.

On Tuesday, Argentina must repay $3.1bn

to the International Monetary Fund

Mr Kirchner has said he will default

on the loan unless he receives prior assurance from the IMF that it will

approve a disbursement linked to the country's three-year agreement that would

cover the loan

Financial Times 8/3 2004

The problem is that the disbursements are dependent on Argentina's continuing to negotiate "in good faith" with its private creditors. Many IMF board members believe the country is not meeting that condition and argue that the programme should be suspended.

Argentina is therefore teetering on the edge of another default - one that could leave bondholders without a deal, the country without access to capital markets and the IMF with substantial defaulted debts on its books (see below).

Mr Lavagna also defends the Dubai offer on the premise that the Argentine case is qualitatively different from others and that the old rules no longer apply. One reason for the difference is the sheer scale of the restructuring. With more than $100bn currently in default, Argentina accrues $700m - about 0.5 per cent of gross domestic product - in past due interest every month.

Further complicating the process is the fact that during the 1990s, when Argentina was held aloft by the Group of Seven industrialised nations as the model for other emerging markets, it issued debt in every conceivable form. The result today is 152 types of defaulted bonds issued across eight jurisdictions in seven currencies.

If the debt is unpaid

By Martin Wolf

Argentina is playing a game of chicken over its obligations to the multilateral financial institutions, above all the International Monetary Fund. So what would happen if neither side swerved and the game ended in a head-on crash?

The IMF has never suffered a loss on its lending, since that can happen only if a country ceases to be a member. But lengthy arrears are not unprecedented. Since the mid-1980s, 25 members have gone into arrears, while five were still in arrears this January - namely, Iraq, Liberia, Somalia, Sudan and Zimbabwe.

Where Argentina differs from the others is in scale, since it is the Fund's third largest debtor, after Brazil and Turkey, owing 15.2 per cent of the Fund's outstanding credit at the end of October 2003.

The head of Argentina's Central Bank has

resigned in

the midst of the country's worst economic crisis in history.

BBC, 9 December,

2002

Argentina bank freeze partly lifted

BBC,

1 June, 2002

Är den keynesianska ekonomin död?

Asienkrisen, Ryssland, IMF och Argentina

Joseph Stiglitz

DN,

12 maj 2002

Mauricio Rojas berättelse om hur välståndslandet Argentina omvandlades till avgrundslandet Argentina. Sjuttio år av snabb tillväxt mellan 1860 och 1930 förbyttes i sjuttio år av stagnation och kaos. Landet, som vid 1900-talets början var rikare än både Frankrike, Italien och Sverige, är i dag en bankrutt nation.

För att denna osannolika utveckling skulle kunna inträffa behövdes både Juan och Evita Perón, och alla de misstag och felgrepp som populismen, nationalismen, protektionismen och en allt mer korrupt statsapparat lyckades genomföra. (RE: Undrar om Rojas nämner något om fast växelkurs?)

Argentina on the road to ruin

With

support, the country could just save itself from a hyperinflationary meltdown.

But there is little hope of it doing so

Martin Wolf Published: April 30

2002 19:49

Citigroup Inc. and six other international

banks have lost $8.5 billion in Argentina

New York, April 23 (Bloomberg)

--

Argentina 'risks financial collapse'

BBC,

22 April, 2002

Argentina

orders bank freeze

BBC19 April, 2002, 23:25 GMT

Argentina has

suspended all banking operations and foreign currency transactions indefinitely

amid fears of a financial collapse.

Cavallo Gets the Bill For IMF and Argentine

Profligacy

By Mary Anastasia O'Grady

Wall Street Journal

2002-04-05

IMF 'to ignore' Argentina cash

plea

BBC, 5 April, 2002

Argentina battles spread of poverty

BBC

2002-04-05

ARGENTINA AND THE FUND:

FROM TRIUMPH TO TRAGEDY

By Michael Mussa Senior Fellow Institute

for International Economics

Washington, DC March 25, 2002, pdf

Argentina bank freeze partly lifted

1

June, 2002

Argentina's President, Eduardo Duhalde, has signed a decree that

outlines a plan to end the controversial and unpopular freeze on bank deposits.

The government imposed restrictions six months ago to stop an anticipated run

on bank accounts which would have triggered the collapse of the entire banking

system.

The government's new plan comes after six months of bitter

complaints about the morality of blocking access to what rightfully belongs to

the people. The banking freeze has kept deposits locked up since last December

to protect the nation's fragile banking industry from collapse. But the

government's plan does not give the public unfettered access to its cash, as so

many have been demanding in daily protests.

Instead, President Duhalde

has offered to swap 30bn pesos ($8.5bn) of deposits for government bonds that

can be converted to cash in either five or 10 years' time.

Är den keynesianska ekonomin död?

Asienkrisen, Ryssland, IMF och Argentina

Joseph Stiglitz

DN,

12 maj 2002

Vi lär av misslyckanden såväl som av framgångsrik ekonomisk politik. När Internationella valutafonden (IMF) tvingade fram stora utgiftssänkningar i Ostasien föll produktionen - precis som keynesiansk teori förutspådde. Tidigt 1998, när jag var chefsekonom på Världsbanken, debatterade jag med det amerikanska finansdepartementet och IMF om Ryssland. De sa att varje stimulans av den ryska ekonomin skulle leda till inflation. Detta var ett anmärkningsvärt medgivande: genom sin övergångspolitik hade de lyckats, på bara några år, minska produktionskapaciteten hos världens andra supermakt med mer än 40 procent, ett för-ödande resultat värre än det av något krig!

IMF lärde läxan anmärkningsvärt långsamt. Medan den sent omsider erkände sitt finanspolitiska misstag i Ostasien, upprepade man det i Argentina och tvingade fram utgiftssänkningar som fördjupade recessionen och drev upp arbetslösheten - till en nivå där allt slutligen föll samman. IMF har ännu i dag inte tillstått sambandet: som villkor för krediter kräver man fortfarande ytterligare nedskärningar. IMF fortsätter att insistera på den alternativa ekonomiska "teori" som Keynes kämpade mot redan för över 60 år sedan. Keynes argumenterade mot föreställningen att om bara länder sänkte sina skulder så skulle "förtroendet" återställas, investeringar öka, och ekonomin återgå till full sysselsättning. Under "IMF-teorin" flockas investerare kring länder där regeringarna föresätter sig att sanera statsskulden, ekonomin får ett uppsving och politiken på så sätt blir rättfärdigad. Regeringens budgetmål uppfylls mer än väl. Den tillfälliga "smärtan" belönas rikligt. Jag känner inte till något land där detta scenario har utspelats framgångsrikt, för det finns två nyckelproblem som belastar "teorin".

Argentina on the road to ruin

With

support, the country could just save itself from a hyperinflationary meltdown.

But there is little hope of it doing so

Martin Wolf Published: April 30

2002 19:49

Argentina is on the edge of an abyss. The peso has sunk from one-to-the- dollar to three-to-the- dollar. From deflation, the country has moved into inflation, with a rise of 4 per cent in the consumer price index for March. The consensus forecast is for inflation at more than 60 per cent from December 2001 to December 2002 and for an 11 per cent decline in gross domestic product this year.

The fiscal revenue position is deteriorating. Given the resistance to cuts in public spending, the public's unwillingness to pay taxes and the government's loss of creditworthiness, the monetary printing press is almost all that remains.

Citigroup Inc. and six other

international banks have lost $8.5 billion in Argentina

New York, April 23

(Bloomberg) --

Citigroup Inc. and six other international banks have lost $8.5 billion in Argentina, 60 percent more than what the banks reported in January, an analysis of first-quarter earnings showed. With $23.6 billion of Argentine loans on their books at yearend, the banks face more losses in the months ahead from the government's peso devaluation and debt default, analysts and investors said.

Argentina 'risks financial collapse'

BBC, 22 April, 2002

Argentina's entire financial system could collapse if the run on

its banks continues, President Eduardo Duhalde has warned.

His comments come a day after all foreign exchange and banking transactions were halted indefinitely.

Cavallo Gets the Bill For IMF and

Argentine Profligacy

By Mary Anastasia O'Grady

Wall Street Journal

2002-04-05

Mary Anastasia O'Grady is editor of The

Americas, which appears every Friday. The column discusses political, economic,

business and financial events and trends in the Americas. Ms. O'Grady is also a

senior editorial-page writer for the Journal, writing on Latin America and

Canada. She joined the paper in 1995 and was named a senior editorial-page

writer in 1999.

Prior to working at the Journal, Ms. O'Grady worked as an

options strategist first for Advest Inc. in 1981 and later for Thomson McKinnon

Securities in 1983. She moved to Merrill Lynch & Co. in 1984 as an options

strategist. In 1997, Ms. O'Grady won the Inter American Press Association's

Daily Gleaner Award for editorial commentary, and in 1999 she received an

honorable mention in IAPA's opinion award category for her editorials and

weekly column. Born in Bryn Mawr, Pa., she received a bachelor's degree in

English from Assumption College in Worcester, Mass. She has an M.B.A. in

financial management from Pace University in New York.

Under the Fund's traditional three-monkeys approach to assessing a

member's performance -- hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil -- such

transgressions would often be ignored."

Michael Mussa, former IMF chief

economist, on how the Fund looked the other way when Argentina used creative

accounting.

The highly politicized arrest this week of former Argentine finance minister Domingo Cavallo on contraband charges dating back to the early 1990s looks like another sign of how far gone Argentina is. In any just universe, the arrest should be the final nail in the coffin of IMF lending to the Argentine government.

Even before Mr. Cavallo went before the judge Wednesday, bad economic news was tumbling out of Argentina like clowns from a circus car. Last week the government tried hard to prop up the battered peso -- which is supposed to be floating -- but the currency remains weak. It now sells for about 35 cents, down from $1 less than four months ago. Prices for staple foodstuffs such as meat and flour are sharply higher; there are shortages of hospital supplies and medicines. Unemployment is close to 25%. Bank deposits are still frozen.

Earlier this week, in a move that reflected the general business environment, Telecom Argentina announced it would suspend principal payments on $3.2 billion in debt.

IMF 'to ignore' Argentina cash

plea

BBC, 5 April, 2002

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is unlikely to release new funds to help Argentina's struggling economy, a report has said.

"This is for their own good and they should understand that."

Argentina battles spread of

poverty

BBC 2002-04-05

Argentina's president, Eduardo Duhalde, has announced fresh measures to relieve poverty. Under the new plan, each unemployed household will from 15 May receive 150 pesos ($50.5) a month.

An economic crisis has rocked Argentina, leaving almost half of the population below the poverty line. And an estimated one-in-five of the country's 36 million people are unemployed.

FT Editorial comment: Argentina on the edge Published: March 26 2002 19:20 | Last Updated: March 26 2002 19:21 Argentina's drift towards default and devaluation lasted the whole of 2001; the subsequent economic implosion has occurred much more quickly. Since one-for-one convertibility with the dollar was abandoned, the peso has fallen by about 70 per cent. After four years of recession, the economy has slumped: output is expected to drop by at least 8 per cent this year. And the economic crisis has further undermined the government's already dreadful fiscal position. Argentines expect the peso printing presses to start rolling; so they naturally clamour for dollars; and this lack of confidence threatens to become self-fulfilling. A collapsing currency guarantees hyperinflation.

Krugman: The natural answer is to float the currency. Some have proposed an alternative - devalue, then dollarize. But it was always strange to peg the peso to the dollar, when the U.S. is by no means Argentina’s dominant trading partner. The peg made sense only as a way to provide clarity and credibility. Since that credibility will be lost anyway by devaluation, why lock the country into an inappropriate currency regime? Argentina’s location and export composition suggest that it should emulate other southern-hemisphere primary exporters, like Australia, and have a floating exchange rate. Now comes the hard part. Isn’t it dangerous to devalue?

Argentina

peso hits new low

BBC, 13 March, 2002

In Argentina, the peso has slipped to a record low amid gloomy predictions that the country's worst ever economic crisis will deepen further this year. Until devaluation in January, the peso was tied to the US dollar at one-to-one for a decade. It has now slipped to 2.5 to the dollar.

Washington Post, Tuesday, March 5, 2002

Argentina is an economic mess. Its banks are broke, surviving by not paying depositors. Its federal and state governments cannot pay employees and suppliers; foreign debt payments are suspended; economic activity has slowed to a crawl; unemployment is heading toward 30 percent; and the nation's health and education systems are reeling.

Argentine crisis shakes faith in democracy

Financial Times

February 26 2002

Politicians are unpopular the world over, but Argentina's rulers have sunk to a level of disrepute probably unparalleled in the country's history. Eduardo Menem, a national senator and brother of the former president, Carlos, recently got a taste of the popular disdain for his profession on a flight to Buenos Aires from his native province of La Rioja. Recognising him, a young man stood up and began shouting: "What an awful smell of shit in here." In the ensuing scuffle, Mr Menem punched the man in the face and the cabin crew had to place the men at opposite ends of the aircraft.

Mr Menem is not the only Argentine politician to feel the ire of a nation enduring its worst economic crisis in recent history. Passengers travelling to Europe recently complained about having to share a flight with Carlos Ruckauf, the foreign minister.

Argentina unveils crisis

package

planned to fully float the national currency on Wednesday

BBC, 4

February, 2002

In a nationwide address, Jorge Remes Lenicov said the government planned to fully float the national currency on Wednesday, ease a hated banking freeze and drastically reduce its budget deficit.

För en handfull

peso

Rolf Englund

Nya Wermlands-Tidningen 2002-01-22

No right answer?

The Economist Jan

21st 2002

No right answer?

The Economist Jan

21st 2002

The turmoil in Argentina and the collapse of the ten-year link between the peso and the dollar has revived the debate about currency regimes for emerging-market economies. Was Argentina wrong to adopt the link in the first place, or wrong to try so hard and so fruitlessly to maintain it?

What do Argentina, Hong Kong, Bulgaria and Bosnia have in common? Not that much, in terms of politics, culture or standard of living. But until a few weeks ago, they did share a controversial economic policy: during the 1990s, all of them introduced currency boards—essentially a system of legally-binding fixed exchange-rates. It is hard to remember just how radical this approach to exchange-rate policy seemed when currency boards came back into fashion many decades after they had last been used. But earlier this month, after weeks of growing political unrest which toppled the government of President Fernando de la Rua, Argentina finally abandoned its currency board and the fixed-parity link between the peso and the dollar.

For months, Argentina had been staring catastrophe in the face. Expectations that the government would devalue the peso and default on the country’s huge public debt were rife. But few could have predicted just how great the crisis would be. Domingo Cavallo, the country’s economy minister until late December, is now a fading memory—even though he had been the driving force to preserve the currency peg, and had indeed been its creator back in 1991. The new President, Eduardo Duhalde, is the fifth man to hold the job in a matter of weeks and has yet to establish a grip on the country’s enormous economic problems. Argentina is now formally in default, and the peso has been devalued by around 40%. But policies to stimulate the economy—now in its fourth year of recession—and to stabilise the banking system have yet to be put in place.

Argentine Banks Insolvent, Face $54 Bln Loss

Buenos Aires,

Jan. 18 (Bloomberg)

Argentine banks are insolvent and face $54 billion of losses—more than twice earlier estimates—after the government devalued the peso and stopped most financial transactions, Moody’s Investors Service said.

The rating agency said President Eduardo Duhalde’s only chance to avert a collapse of the banking system may be to convert all dollar deposits into pesos, a plan opposed by most Argentines. Otherwise, the government will be forced to take control of banks, turn deposits into peso bonds and try to sell the banks, Moody’s said in a report.

Argentina visar att EMU inte

räcker

Gunnar Örn

Dagens Industri 2002-01-14

Rolf Englunds anmälan till

Granskningsnämnden för radio och TV av

God morgon

Världens inslag om Argentina 2002-01-13

2002-01-14

Argentina lashes out at IMF

BBC

2002-01-13

Duhalde's wrong turn

Jeffrey Sachs

Financial Times January 10 2002 20:28

The writer is professor of

economics and director of the Centre for International Development at Harvard

University

En hårdhänt läxa för

Argentina

Joseph Stiglitz

Kolumn i DN 2002-01-11

Argentina’s devaluation

From

straitjacket to padded cell

The Economist, Jan 12 2002

Argentina Freezes More Than a Third of

Deposits

Buenos Aires, Jan. 10 (Bloomberg)

Argentina – ett fiasko för

liberalismen?

Fredrik Erixon, chefekonom i Timbro

Det finns

anledning att gråta för Argentina.

Carl Bildts veckobrev

v1/2002

Argentina är en annan

historia

DN-ledare 2002-01-05

Argentina devalues currency by 29%

Financial Times, January 6 2002 20:52

The Economist 2001-03-22

Argentine banks stare bankruptcy in the

face

Financial Times, January 8 2002 19:42

GRANSKNINGSNÄMNDEN FÖR RADIO

OCH TV

BESLUT 2002-03-25 - Dnr 45/02-30

SAKEN

Godmorgon världen, P1, 2002-01-13, inslag om Argentina; fråga om saklighet

Inslaget handlade om Argentinas akuta ekonomiska kris. Inslaget inleddes med ett reportage från Buenos Aires där intervjuade argentinare uttalade sig om sin syn på krisen. Därefter intervjuades två experter - en forskare vid Stockholms Universitet och en internationell ekonomisk politisk rådgivare. De redovisade sin syn på orsakerna till krisen och anförde därvid bl.a. den politiska krisen och Argentinas sätt att låna pengar på världsmarknaden genom att utfärda obligationer. Argentinas fasta växelkurs mot USA dollarn nämndes inte särskilt i kommentera och analyserna.

Anmälaren anser att inslaget strider mot kravet på saklighet genom att Argentinas fasta växelkurs mot dollarn inte nämndes som en orsak till landets ekonomiska kris.

Granskningsnämnden kan inte finna att enbart den omständigheten att Argentinas fasta växelkurs mot USA dollarn inte angavs som en orsak till den ekonomiska utvecklingen i landet innebär att inslaget strider mot kravet på saklighet i Sveriges Radios sändningstillstånd.

Detta beslut har fattats av Granskningsnämndens direktör Greger Lindberg efter föredragning av Hack Kampmann.

Stockholm 2002-01-14

Granskningsnämnden för radio och TV

God morgon Världens inslag om Argentina 2002-01-13

Aldrig hade jag väl trott att jag skulle anmäla Godmorgon Världen för Granskningsnämnden. Godmorgon Världen är ju enligt min mening radions bästa program.

God morgon Världens inslag om Argentina ställer emellertid också en viktig principiell fråga om hur man skall tolka reglerna om saklighet.

När det gäller reglerna för opartiskhet brukar det hävdas att ett program visserligen kan vara vinklat på ett sätt som kan vara partiskt, men att detta uppvägs av radions program i övrigt.

Frågan är om detta synsätt även kan användas på ett program vad avser kravet på saklighet. Kan ett program måste vara osakligt även om det finns andra program i samma ämne som är sakliga?

Bristen på saklighet i det aktuella inslaget är att det inte nämner Argentinas fasta växelkurs. Det var inte ens en påannons av typen “ det har talats mycket om den fasta växelkursen som orsak till Argentinas kris, men det finns även andra förklaringar...”.

Förvisso råder det korruption i Argentina. Likaledes är den politiska kulturen inte lika framstående som i Sverige. Det kan väl ha sin betydelse. Men det är väl inte mycket bättre i grannländerna Brasilien, Uruguay och Bolivia.

I programmet nämndes inte någonting om att Argentina har haft en fast växelkurs, liknande den Sverige hade fram till hösten 1992.

Som framgår av den allmänna debatten har utvecklingen i Argentina också diskuterats i samband med EMU, som innebär den fastaste växelkurs man kan tänka sig.

I den allmänna debatten, såväl i Sverige som internationellt, har den fasta växelkursen mot dollarn enligt teorin 1 Peso = 1 Dollar varit avgörande för de senaste årens ekonomiska utveckling i Argentina.

En del av debatten kan man nå via

www.nejtillemu.com/argentina.htm

Att i programmet helt utelämna detta står således i bjärt, jag tvekar inte att använda ordet eklatant, kontrast mot övriga seriösa analyser och strider därför, enligt min mening, mot reglerna om saklighet.

Härmed anmäls därför rubr. program för brott mot reglerna om saklighet.

Argentina visar att EMU inte

räcker

Gunnar Örn

Dagens Industri 2002-01-14

Om Argentina hade varit ett europeiskt land, skulle argentinarna inte haft några problem med att kvala in i den europeiska valutaunionen EMU redan från starten. Eftersom Argentina nu befinner sig i ekonomiskt kaos väcker det frågor om stabiliteten i EMU.

Argentina klarade samtliga fem inträdesprov med god marginal 1997, det år som gällde som provår för kandidatländerna:

Högst 2,7 procents inflation.

Priserna i Argentina steg med 0,5 procent. Inget europeiskt land hade lägre inflationstakt.

Budgetunderskott på högst 3 procent av BNP.

Det samlade underskottet i Argentinas offentliga finanser motsvarade 2,4 procent av landets bruttonationalprodukt. Hälften av de blivande euroländerna, bland dem Tyskland och Frankrike, hade större underskott.

Offentlig bruttoskuld på högst 60 procent av BNP.

Argentina hade en offentlig skuld motsvarande 40 procent av landets BNP år 1997. Bland de elva blivande euroländerna var det bara Luxemburg som var mindre skuldsatt.

(Italien och Belgien låg skyhögt över 60-procentsstrecket. De blev ändå insläppta i valutaunionen med argumentet att skuldkvoterna utvecklades åt rätt håll.)

Högst 7,8 procents lång ränta.

Detta är det enda konvergenskrav Argentina hade svårt med. Under provåret betalade landet i genomsnitt 8,0 procents ränta på sina långfristiga obligationslån i tyska mark. En högre räntenivå än i något EU-land med undantag av Grekland.

Men Argentinas låga inflation hade hjälpt landet att klara även detta inträdesprov.

Enligt Maastrichtfördraget får långräntan vara "högst 2 procentenheter över den genomsnittliga räntenivån i de tre länderna med den lägsta inflationen".

Eftersom Argentina platsade bland dessa tre, skulle landets kandidatur ha höjt maxvärdet till 8,4 procent. Därmed hade argentinarna klarat även ränteprovet med hygglig marginal.

Fast växelkurs i två års tid.

Argentina kunde upprätthålla sin fasta växelkurs mot dollarn under åren 1996 och 1997 utan några allvarliga störningar.

Då dollarn överlag stärktes under denna period, hade det till och med varit lättare för argentinarna att i stället hålla en fast växelkurs mot någon europeisk valuta.

Då är frågan: Hur kan ett land, som var överkvalificerat för EMU 1997, drabbas av statsbankrutt och ekonomiskt kaos bara några år senare?

Alla länder har förstås sina egna unika problem, men vad som är uppenbart i Argentinas fall är att de egna problemen förvärrats av att landet inte kunnat föra någon självständig ränte- och valutapolitik.

Argentina har haft sin peso helt låst mot den amerikanska dollarn. Båda valutorna har använts parallellt. Den som betalat med pesos har kunna få växel i dollar och tvärtom.

På så sätt påminner Argentina om euroländerna, som också gett upp sin självständiga penningpolitik då de avskaffat sina egna valutor till förmån för euron.

Syftet med konvergenskraven och stabilitetspakten har varit just att förhindra "tangokriser" i EMU. Länder vars finanser är misskötta, eller vars ekonomier är helt ur fas med de övrigas, ska inte släppas in i valutaunionen.

Framför allt Tyskland har hållit hårt på konvergenskraven. Detta av djupt rotad rädsla för inflation.

Skulle ett EMU-land drabbas av en statsbankrutt i argentinsk stil, kan Europeiska centralbanken tvingas låta sedelpressarna rulla i syfte att rädda landets fordringsägare och hindra finanskrisen från att sprida sig över hela Europa.

Men om konvergenskraven inte kunda hindra tangokrisen från att bryta ut, vad är det då som säger att de skulle kunna hindra en "flamencokris"? Eller varför inte en "Riverdance-" eller "valskris"?

Exemplet Argentina visar att de nuvarande säkerhetsarrangemangen i EMU, med konvergenskrav och stabilitetspakt, inte räcker för att hindra ett medlemsland från att köra sin egen ekonomi i botten.

Argentina lashes out at IMF

BBC

2002-01-13

The IMF had asked Argentina to come up with what it called a more coherent economic policy.

The Argentine Government needs the IMF’s support to tackle its economic crisis. But at the same time it is trying to placate an angry and impatient population which probably would not take much more of the kind of hard monetarist policies the IMF would recommend.

The IMF has said that Argentina must present what it called a more coherent economic policy if it is to gain its support.

Foreign investors have already expressed their concern at what they see as the government’s protectionist policies and others have said that Argentina’s new dual currency system is unworkable.

Duhalde's wrong turn Jeffrey Sachs

Financial Times January 10 2002 20:28

The writer is professor of

economics and director of the Centre for International Development at Harvard

University

The case for devaluation is clear enough. The Argentine peso was not only under attack; it was overvalued. For once, the speculators had a clear foothold in macroeconomic reality. Once Brazil's overvalued currency was allowed to depreciate in February 1999, Argentina's currency board simply lost its credibility.

The economy plummeted into recession as manufacturers shut up shop or shifted operations to Brazil. The refusal by Fernando de la Rua's government to adjust the currency board left the economy in free fall.

It is true that past breaks from pegged rate systems have led to renewed economic growth, most notably in Mexico in 1994, Russia in 1998 and Brazil in 1999.

But Argentina's remarkable history of monetary mischief makes it an exceptional case. I do not know another nation with Argentina's capacity to abuse, manipulate, freeze, confiscate and periodically replace the national currency and the contracts set in it. The currency board was introduced precisely to break this record.

Dollarisation would have ended it decisively.

En hårdhänt läxa för

Argentina

Joseph Stiglitz

Kolumn i DN 2002-01-11

Joseph Stiglitz är professor i ekonomi vid Columbiauniversitetet, har varit ordförande i president Clintons ekonomiska råd och chefsekonom och vice ordförande i Världsbanken

Kollapsen i Argentina har lett till den största konkursen i världshistorien. Att förstå vad som gick fel kan lära oss mycket inför framtiden.

Problemen inleddes med hyperinflationen på 1980-talet. För att få ner inflationen måste Argentina förändra förväntningarna på ekonomin, och genom att knyta peson till dollarn försökte man göra just detta. Denna modell fungerade under en tid i vissa länder, men inte utan risker. Det har vi nu sett tydligt i Argentina.

Internationella valutafonden uppmuntrade detta system. Nu är de mind-re entusiastiska, även om det är Argentina och inte IMF som får betala priset. Den bundna pesokursen minskade visserligen inflationen, men den minskade också tillväxten.

Argentina borde ha uppmuntrats till ett mer flexibelt växelkurssystem eller åtminstone en växelkurs som bättre stämde överens med dess handelsmönster.

Detta var emellerltid inte det enda misstaget i Argentinas reformprogram. Landet prisades länge för att det tillät stort utländskt ägande i banksektorn. Under en tid skapade detta ett stabilt banksystem, men bankerna lånade i liten utsträckning ut pengar till små och medelstora företag.

Krisen i Sydostasien 1997 var det första slaget. Delvis därför att krisen där på grund av IMF:s dåliga handhavande blev en global kris, som höjde räntorna i alla tillväxtmarknader, inklusive Argentina.

Argentinas växelkurs överlevde, men till priset av en dubbelsiffrig arbetslöshet. Snabbt kvävde också de höga räntorna landets finanser.

Trots att Argentinas statsskuld aldrig var mer än 45 procent av BNP, betalade man 9 procent av BNP årligen på lånen.

Den globala krisen ledde också till att växelkurserna i världen omvärderades. Dollarn, som peson var knuten till, stärktes kraftigt.

Samtidigt föll grannlandet Brasiliens valuta kraftigt. Löner och priser föll, men inte tillräckligt för att Argentina skulle kunna konkurrera, speciellt som många av dess exportprodukter inom jordbruket är högt tullbelagda i rika länder.

Världen hade knappt hämtat sig från finanskrisen 97-98 förrän den globala lågkonjunkturen började sätta in 2000-2001, vilket gjorde Argentinas situation än mer prekär. Då gjorde IMF ett fatalt misstag.

Organisationen uppmuntrade statsfinansiell åtstramning, samma medicin som ordinerades under Asienkrisen, med samma fruktansvärda följder.

Strängheten förväntades återskapa förtroendet för ekonomin. Men siffrorna i IMF:s kalkyler var fantasier, vilken ekonom som helst skulle ha sett att åtstramningar i detta läge skulle förvärra konjunkturvändningen och leda till budgetunderskott.

Kanske skulle en militärdiktator, som Chiles Pinochet, ha kunnat undertrycka den sociala och politiska osäkerhet som uppstår när en ekonomi råkar i fritt fall. Men i Argentinas demokrati gick inte det. Det är närmast en överraskning att det tog så lång tid innan de usla levnadsförhållandena ledde till de upplopp som nu tvingat bort flera presidenter.

LÄXOR MÅSTE vi dra av detta:

1. I en värld med flytande växelkurser är det extremt riskfyllt att knyta sin valuta till exempelvis dollarn. Argentina borde ha manats att bryta dollarbindningen för flera år sedan.

2. Globaliseringen gör att länder kan utsättas för stora chocker. Länderna måste hantera dessa chocker och förändringar i växelkursen är ett sådant sätt.

3. Att ignorera sociala och politiska faktorer sker på egen risk. En regering som för en politik som lämnar stora delar av befolkningen arbetslös har misslyckats med sitt huvudsakliga uppdrag.

4. En ensidig inflationsbekämpning, utan tankar på arbetslösheten, är riskabel.

5. Tillväxt förutsätter finansiella institutioner som lånar ut pengar till lokala företag. Att sälja alla banker till utländska ägare och mista kontrollen kan minska tillväxt och stabilitet.

6. Det är svårt att återskapa ekonomisk styrka med en politik som driver fram en djup lågkonjunktur. Genom att insistera på åtstramningar har IMF ett stort ansvar.

7. Det krävs bättre sätt att hantera kriser som den i Argentina. IMF har föredragit att lösa ut krisdrabbade länder med stora lån. Nu har de äntligen insett att man måste ha alternativ.

IMF KOMMER ATT försöka lägga skulden på Argentina - det kommer att bli anklagelser om korruption och om att Argentina inte vidtagit rimliga åtgärder. Självfallet behövde landet genomföra andra reformer, men genom att följa IMF:s råd om åtstramningspolitik gjorde man illa värre.

Devaluation's downbeat start

From The Economist print

edition

Jan 10th 2002

The measures leave the banksmost of the big ones are foreign-ownedstaring at huge losses. To compensate, they will receive the proceeds from a new tax of up to 20% on oil and gas exports (the main exporter, Repsol, is Spanish). That will not be enough to save many of the banks. As well as having many of their loans but not their deposits devalued, the banks will lose in other ways.

Their bad debts will rise, as many larger debtors (whose loans remain in dollars) default. And secondly, the banks hold many government bonds, now worth little. The bankers claim they will lose more than $10 billion from turning loans into pesos, or more than half their total capital of $17 billion.

Argentina’s devaluation

From

straitjacket to padded cell

The Economist, Jan 12 2002

After a decade in which Argentina lived with a fixed exchange rate and an increasingly dollarised economy, a devaluation of the peso was always going to be traumatic. That was why it was put off for so long.

Jose Maria Aznar, Spain’s prime minister, pointedly called this week for Argentina to agree with the IMF on a “credible” new plan. He is right, even if both he and Felipe Gonzalez, a former prime minister, have been foolish to act as lobbyists for Spain’s “national champions”, the banks and utilities that have reaped rich rewards from their investment of $40 billion in Argentina over the past decade.

Nonetheless, the main cause of Argentina’s troubles was homegrown: the combination of a fixed exchange rate, fiscal profligacy and mounting debt is not “neo-liberal”. It is simply bad policy-and all the more reason to avoid a different set of bad policies now.

Argentina – ett fiasko för

liberalismen?

Fredrik Erixon, chefekonom i Timbro

Kollapsen är ett misslyckande, inte bara för argentinarna utan också för USA, IMF, G7 och flera andra inblandade parter utanför Latinamerika. Men den är inte ett misslyckande för en liberal ekonomisk politik. Tvärtom. Krisen bygger i mångt och mycket just på bristen av kapitalism och ekonomisk liberalism.

Rapporteringen från krisen i Argentina har ofta handlat om dess sedelfond. Mycket riktigt har sedelfonden också varit ett av de stora problemen i Argentina de senaste åren. Men det var inte som ett problem den tillkom, utan som lösningen på ett problem – Argentinas hyperinflation.

Sedelfonden är en fast växelkursregim som bygger på att en växelkurs mellan två valutor ska hållas konstant. Men den skiljer sig från det monetära system Sverige hade med knytning till ecun fram till början på 1990-talet. Den svenska regimen, liksom många andra valutaregimer under samma tid, var snarare en halvfast växelkursregim som bygger på att ett land knyter valutan till en annan storhet, vanligtvis en annan valuta, och använder penningpolitiken till att försvara att det värdet behålls.

En sedelfond innebär en starkare knytning till en annan valuta, genom att det land som inför sedelfonden ger upp stora delar av en centralbanks arbete, för att i stället bygga på principen att, som i Argentinas fall, varje peso som ges ut också har ett motsvarande värde i centralbankens reserver.

Med andra ord: Argentina försvarade inte knytningen av peso till dollarn genom att stödköpa eller -sälja argentinska pesos, utan genom att varje peso som fanns i omlopp kunde inväxlas mot en dollar.

IMF:s relation till Argentina är ett typiskt exempel på hur IMF inte bör uppträda. Inte på grund av att de stundtals gett dåliga råd till hur Argentinas ekonomi bör skötas, utan på grund av att institutionen själv bidrar till en oansvarig ekonomisk politik.

Om man räknar på hur stor del av tiden sedan det första IMF-programmet kom 1957 som IMF har funnits på plats med lån i Argentina blir resultatet alarmerande. I 37 år, cirka 75 procent av tiden sedan dess, har IMF lånat pengar till Argentina.

Sedan 1983 har 15 olika ”räddningspaket” givits.

Syftet med IMF är inte att vara en ständig långivare, utan en sista långivare som länder kan vända sig till om de står inför finansiell kollaps som hotar betalningssystemet och den finansiella stabiliteten. Man har snarare sett till att omvärlden blivit beroende av IMF, inte minst efter Bretton Woods-systemets fall i början på 1970-talet, då IMF:s uppdrag egentligen försvann, och med räddningsaktioner började skapa vad ekonomer kallar för ”moral hazard” (moralisk risk), det vill säga att investerare och politiker inte behöver ta konsekvensen av att agera riskfyllt och oansvarigt.

Bush-administrationen ville ändra på den av Clinton och Robert Rubin fastslagna policyn för räddningsaktioner (bailouts) som växte dramatiskt i antal under 1990-talet.

USA:s finansminister Paul O’Neill torgförde också under sin första tid en djupt grundad skepsis mot IMF; den finns förvisso kvar, men den har dämpats av att Vita huset gått emot finansministeriets rekommendationer i fallet Argentina och givit förnyade lån till landet, senast i augusti i fjol.

Argentina Freezes More Than a Third of

Deposits

Buenos Aires, Jan. 10 (Bloomberg)

Argentina froze certificate of deposit accounts, or more than a third of the nation's $67 billion savings, to protect banks from collapse and avert a plunge in the peso once trading resumes tomorrow.

The government, which published the plan in its official bulletin, banned withdrawal of dollars in CDs for as long as 21 months. Peso-denominated CDs can't be accessed for a year.

Argentine banks stare bankruptcy in the face

Financial Times, January 8 2002 19:42

According to many analysts, the country's banking system will shortly be bankrupt itself.

"Our worst-case scenario would see the capital of all local banks wiped out," said Inigo Lecubarri, banks analyst at Schroder Salomon Smith Barney. "That does not look so unlikely now. The financial system is not looking pretty."

But even a relatively benign estimate of the costs the banks face would leave them unable to function. Merrill Lynch estimates the losses at $10bn-$12bn, wiping out most of the $17bn of capital the banks have.

"It is at a stage where the financial system cannot operate," said Jose Luis de Mora, banks analyst at Merrill. "They need an international bail-out."

RE: Otherwise Merrill may lose a lot of money

How Argentina Got Into This Mess

By

Brink Lindsey

Mr. Lindsey is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute

and the author of "Against the Dead Hand: The Uncertain Struggle for Global

Capitalism" (John Wiley & Sons, 2002).

Wall Street Journal,

2002-01-09

How Argentina Got Into This Mess

By Brink

Lindsey

Mr. Lindsey is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute and the

author of "Against the Dead Hand: The Uncertain Struggle for Global Capitalism"

(John Wiley & Sons, 2002).

Wall Street Journal, 2002-01-09

It is fashionable now to blame Argentina's problems on the free market. The country's latest president, old-school Perónist and unabashed protectionist Eduardo Duhalde, has joined the anti-market chorus by vowing to break with the "failed economic model" of the past decade. But Argentina's tragic crack-up occurred not because pro-market reforms went too far, but because they did not go nearly far enough.

Note: Check in the full article if You can find the words fixed exchange rate or peg or 1 Peso = 1 Dollar. I could not.

Se även Mats Svegfors http://www.internetional.se/sveg9409.htm

Argentina devalues currency by 29%

Financial Times, January 6 2002 20:52

Argentina on Sunday devalued its currency by nearly 29 per cent as European governments appealed for their companies to be protected from the fallout.

The new "official" peso rate will be 1.40 to the US dollar - broadly in line with expectations - with the currency floating on unofficial markets from Monday. The government said its objective was to free the currency entirely in less than six months.

Jorge Remes Lenicov, economy minister, conceded that the International Monetary Fund had objected to the dual exchange rate plan.

"I spoke with the people from the Fund . . . who said that, philosophically, they consider that a float [of the peso] is preferable," he said.

Argentina’s desperate choices

The Economist 2001-03-22

IT IS fitting that Domingo Cavallo should have been drafted in this week as Argentina’s new economy minister—the third person to hold that job this month. He is now seen as the only man capable of maintaining the currency-board system that he set up a decade ago.

That system pegs the peso by law at parity to the dollar and, in effect, hands monetary policy over to the United States Federal Reserve. Not only has the device killed hyperinflation; for much of the 1990s, it delivered strong growth. But Argentina’s economy has now been locked in a recession for almost three years. The currency board has become a straitjacket.

In January, President Fernando de la Rua’s Alliance government thought it had at last found the key. An agreement with the IMF, involving loans and credit guarantees amounting to $39.7 billion, seemed to offer a respite. So did cuts in American interest rates and a (temporary) weakening of the mighty dollar, and thus the peso.

The economy, however, did not pick up, though the fiscal deficit did. With markets twitchy, Mr de la Rua turned to Ricardo Lopez Murphy, a free-market economist from his Radical party. Mr Lopez did as he was asked: on March 16th, he announced budget cuts of $2 billion this year, and $2.5 billion in 2002. But over half the proposed cuts were in education spending, prompting three ministers, and six other senior officials, to resign, and Frepaso, the Alliance’s junior (and more left-wing) partner, to walk out of the government.

Argentina’s drama is that it has almost run out of room for economic manoeuvre. On the one hand, the strength of the dollar has made it hard for Argentina’s exports (only 11% of which go to the United States) to compete, especially after Brazil, its main trading partner, devalued in 1999. The economy has had to adjust through deflation: prices and wages have fallen. That has simply prolonged the recession.

Nor can the government freely use fiscal policy to kick the economy into action. Fiscal profligacy in the later years of Mr Menem, Mr de la Rua’s predecessor, meant that Argentina piled up debt, which now stands at close to 50% of GDP. Argentina is now in a vicious circle.

The political fragility of Mr de la Rua’s government has worried investors, forcing up interest rates, which depress growth and add to the debt burden, while the recession means tax revenues are falling.

So what can Mr Cavallo do? Abandoning the currency board would still be the most expensive option, because the economy is already partly dollarised. Firms would be destroyed by the burden of their dollar debts, intensifying the recession.

Mr Cavallo may seek to use his reputation to persuade Wall Street and the IMF to back a rescheduling of Argentina’s debts (or, if you prefer, a default).

Wish him well, though. Failure would mean that Argentina would almost certainly find itself heading for a unilateral debt default, which might increase the cost of credit in all emerging markets. Meanwhile, if some bright economist should argue that currency-boards are a miracle cure for any unstable third-world country, irrespective of its circumstances, show him the door.

Cavallo's reforms may have removed exchange rate risks but economic and political instability are less susceptible Martin Wolf, Financial Times, March 21, 2001